- by foxnews

- 08 Apr 2025

The 'sadmin' after my mother’s death was hard enough - then I encountered Vodafone | George Monbiot

The 'sadmin' after my mother’s death was hard enough - then I encountered Vodafone | George Monbiot

- by theguardian

- 30 Jul 2022

- in technology

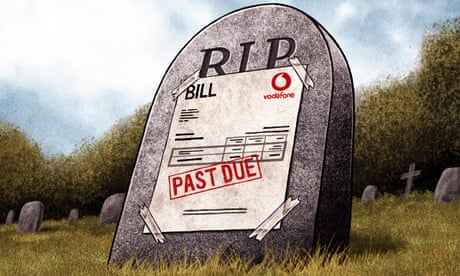

It's sometimes called "sadmin": tying up the affairs of someone who has passed away. There's a lot to do, though some aspects have become easier - you can notify most branches of government through an online form called Tell Us Once. But some private interests are less helpful.

My mother died in early March. My father is confused and very frail, so my sister and my dad's carer and I handled the sadmin. Most of it went smoothly: in many cases cancelling my mother's accounts was quick and straightforward. That was until we ran into Vodafone.

A long time ago my father set up two Vodafone contracts, one for himself and one for my mother. He stopped using his phone a few years ago, and we cancelled his contract. But my mum used hers almost until the end of her life. After she died, we followed the only available route, and rang the company. Or tried, dozens of times, before giving up after 40 or 50 minutes waiting for someone to answer.

When my dad's carer managed at last to speak to a human being, the person who answered was astonishingly rude and unhelpful. He passed us around the system, but no one seemed willing to cancel the contract. We assumed we had caught someone on a bad day, but every encounter, on the rare occasions when someone picked up the phone, followed the same pattern: breathtaking aggression and hostility, followed by stonewalling.

They kept demanding to speak to my father, and refused to hear answers from anyone else, even after we pointed out that my sister and I have lasting power of attorney. The only way we could meet this demand was to dictate the answers to him, which he repeated to the call handler. This caused him great stress and anxiety. Among other questions, they asked him the exact date on which the account commenced. They might as well have asked how many grains of sand there are in the Sahara. When he was unable to answer (none of us knew), they refused to cancel the account.

My mum suffered a long and debilitating illness, and we were as prepared for her death as anyone can be. We are blessed with the support of my dad's brilliant carer. Even so, Vodafone made everything much worse. I can scarcely imagine how this might have affected a family unexpectedly bereaved, under great stress and with fewer resources.

A fortnight ago, more than four months after my mother's death, I belatedly snapped, and described our experience in a Twitter thread. My intention was to shame Vodafone into action. I got more than I bargained for.

Immediately, the responses started pouring in: first dozens, then hundreds of people sharing similar and sometimes even worse experiences when trying to cancel accounts with Vodafone, especially the accounts of people who had died or whose capacity had diminished. They reported, while in the depths of grief, the same nastiness and lack of sympathy. They reported an insistence on questioning vulnerable and confused elderly people. They described months, in some cases years, of failure to cancel such contracts. One woman who contacted me said she was still paying �78 a month to Vodafone for the phone of her daughter, who was murdered more than a year ago, despite sending them the death certificate and newspaper clippings.

Many told me they had also been referred to debt collectors when they stopped their direct debits. Some then discovered, often much later and at crucial moments (such as when trying to buy a house), that their credit rating had been damaged, and they could not proceed until it had been resolved.

A remarkable number of people reported that call handlers insisted on speaking to the deceased account holder "because only the account holder can cancel the account". Some of the responses were grimly funny: people asked the company whether it could supply a medium or suggested exhumation. Other people related similar treatment by a range of phone, finance and utility companies.

When our story went public, Vodafone couldn't move fast enough. After it had checked the details, it cancelled the contract in the course of a two-minute phone call, later the same day. It shows it can be done. It failed to call off the debt collectors, however, who continued to ring my dad until we publicly complained again.

Vodafone did not deny what happened to us. But nor did it respond as I'd hoped. Without consulting me, it issued a public apology to my family for its "errors" and sent me links to information available on its website about cancelling contracts after a bereavement. I found it hard to see this pattern of behaviour, suffered by so many, as "errors", not least because this isn't the first time such practices have been brought to the company's attention. Nor did I want an apology only for my own family, but for all the people who had been treated this way. Above all, I wanted action.

I asked for a call with the chief executive, and was offered a face-to-face meeting, which will happen in September. I have sent the company a list of 21 demands, ranging from joining a one-stop service to compensation for people who have been unfairly charged and wrongly pursued by debt collectors. I won't stop till they have all been met.

When I asked Vodafone whether it had a strategy of exploiting bereaved families, it replied: "We do not have a policy of making it difficult for bereaved families to get in touch with us to cancel contracts." It also told me: "We are conducting a full-scale review and have refreshed the training we provide to our customer care colleagues."

I don't bear grudges. I would be happy to help Vodafone turn its performance around. But, if the company fails to make the necessary changes, I will not stand by and watch.

- by foxnews

- descember 09, 2016

Ancient settlement reveals remains of 1,800-year-old dog, baffling experts: 'Preserved quite well'

Archaeologists have recently unearthed the remarkably well-preserved remains of a dog from ancient Rome, shedding light on the widespread practice of ritual sacrifice in antiquity.

read more