- by foxnews

- 23 May 2025

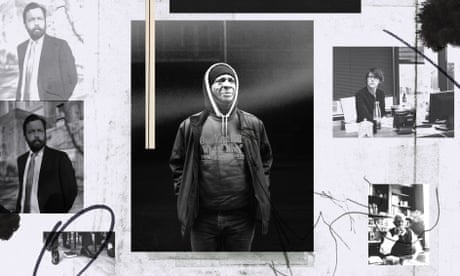

Life in prison for stealing $20: how The Division is taking apart brutal criminal sentences

Life in prison for stealing $20: how The Division is taking apart brutal criminal sentences

- by theguardian

- 08 May 2022

- in news

He had been convicted of stealing $20 in cash from a snatched purse.

His youth had been punctuated by a series of convictions for minor crimes in which no one was physically hurt and a grand total of $44 was taken and later returned. He was involved in the theft of some stereo equipment aged 19. A purse at the age of 21. And at 27, he took an umbrella from a front porch. It was, he recalled, raining that day.

Lewis was convicted of burgling an inhabited dwelling and sentenced to 80 months in prison.

Using his prior record, the city of New Orleans deemed that Maurice Lewis should die in prison after the final purse snatching offense in 1998, in which he had pleaded not guilty.

Nowhere in the state were they as readily enforced as in New Orleans, where prosecutors used them routinely for decades, first at the instruction of former DA Harry Connick and continuing into the tenure of Leon Cannizzaro. Although in recent years the Louisiana state legislature has amended the laws to reduce mandatory sentences and later made it harder for prosecutors to enforce them as vigorously as before, there are still hundreds of people incarcerated, with their sentences enhanced by multi-billing.

At the beginning of 2021, at least 718 people from Orleans parish were still incarcerated under sentences extended by the habitual offender statute. Ninety-three per cent of them are Black.

During a recent meeting of the civil rights division, Cormac Boyle, one of only two trial attorneys assigned to the unit in its first year, began reading from an extensive list of cases they were preparing to take back to court.

It was a sobering monologue:

Life without parole for a non-violent car theft.

60 years for possession with intention to distribute 2.4 grams of cocaine.

20 years for theft of a motorized dirt bike.

40 years for purse snatching. (The man, sentenced in 1986, had almost completed his sentence in full.)

The list drew occasional gasps from the assembled attorneys and investigators. Some, like Boyle, have worked for years on similar cases, but the sheer volume of severity has remained striking to almost everyone.

A few weeks after his release, Maurice Lewis was struggling. He had been overjoyed as he came out and saw his sister and brother at the gates of Angola waiting to greet him. But the realities of life outside grew day by day.

grew

He met with family members; aunts and uncles, nieces or nephews who had grown old or grown up during his decades behind bars. It was a confronting reality.

He was living with his younger brother Eugene in a small apartment block, but with little space, he was sleeping in the living room. Every morning he woke up facing a life-sized photograph of his mother, Alise, who had died while he was in prison.

In conversations, he offered fragments of the abuse he experienced inside: of violence he witnessed, men beaten with padlocks wrapped in socks in the dorms, of a time he recalled being placed in restraints after a breakdown following the death of his mother.

But did he recognize that many of those he was prosecuting under the statute, like Maurice Lewis, were involved in crimes born of poverty and desperation?

It was, he said in a recent interview, one of the hardest decisions he has had to make in office.

On a bright Sunday morning in spring Maurice Lewis sat in church, his head bent in prayer and his right arm lifted to the heavens. He had come to worship at the Next Generation Original Morning Star, in a congregation made up mostly of formerly incarcerated people. It was his first Sunday service since release.

Pastor Tyrone Smith led the worshippers in a rendition of Amazing Grace. It soared to the rafters and had the congregation swaying in time. It reminded Lewis of his mother again. The hymn had been played at her funeral, which he could not attend.

Pastor Smith, himself formerly incarcerated, is co-director of the First 72+, a non-profit organization that assists people with re-entry. Lewis had received some assistance from the group, but even now, four months after release, he was struggling to navigate the complex bureaucracy to regain some of the documentation he required to claim income assistance or apply for jobs.

There is little to no state assistance for those leaving prison in Louisiana, meaning non-profits like the First 72+ and individual family members shoulder much of the burden assisting those who re-enter society.

At the end of last year the division secured a $1m federal grant to assess and bolster re-entry services in the city.

Lewis has tried to remain optimistic ever since his release and drew strength from the hour of church. He aspired to work in a local hospital, a cleaning job perhaps, anywhere surrounded by people, where he could contribute.

Additional reporting by Katie Jane Fernelius

- by foxnews

- descember 09, 2016

United Airlines flight returns to Hawaii after concerning message found on bathroom mirror; FBI investigating

United Airlines Flight 1169 to Los Angeles returned to Hawaii after a "potential security concern" aboard the plane. The FBI and police are investigating.

read more