- by foxnews

- 23 May 2025

Labor and the Liberals are waging an election meme war - but what is the point?

Labor and the Liberals are waging an election meme war - but what is the point?

- by theguardian

- 01 May 2022

- in news

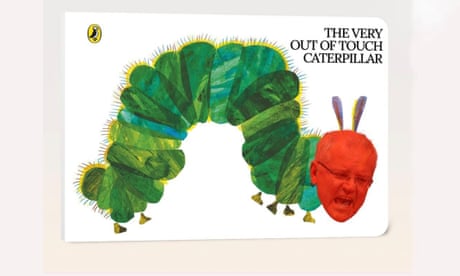

You wouldn't normally expect political parties to prioritise messages about The Simpsons, SpongeBob SquarePants and Judge Judy in the midst of an election campaign. But as Scott Morrison and Anthony Albanese duke it out on debate stages with their competing visions for Australia, there's a battle of a different kind happening online; a battle for attention, eyeballs and shares.

A fascinating meme war is being waged, and it might be more important than you think.

"The parties hope they're funny, but if not they hope they're 'cringe' or infuriating - in hopes of making people feel something," said Jordan McSwiney, a postdoctoral political researcher at the University of Canberra.

Across Facebook and Instagram, Twitter and TikTok, the Liberal and Labor parties are carpet-bombing social media feeds with dozens of posts a day. There's the standard policy announcements, videos of press conferences and happy snaps from fluffy photo ops. But for every graph on wage growth, there's a Star Wars meme with a cutout of Anthony Albanese's face slapped on it; for every soft-focus video of a politician with their family, there's a Labor gag about Scott Morrison not taking responsibility.

Unsurprisingly, humour rates better than dry policy announcements. On Labor's Instagram page, Simpsons references and callbacks to popular meme formats regularly score three to five times the number of likes than press conference clips or political attacks. But in a political campaign, where most decisions are taken back to the essential question of "will this give us a better chance of winning?", it's fair to wonder why highly paid party operatives have factored cartoon memes into their intricate communications strategies.

"None of these things individually will change minds, but if you have a steady trickle of content coming through with a message, gradually that might adjust your perception," said Prof Axel Bruns, a social media and communications researcher at the Queensland University of Technology.

"The message might be 'Albanese's not up to the job'. If I see it repeated and repeated in different versions, with different arguments, maybe gradually I'll start to believe it or have doubts about him."

The term "boomer memes" became a sensation after the 2019 election, with the Liberal party enlisting the New Zealand digital marketing agency Topham Guerin to spearhead a so-called "24-hour meme machine" to blanket social media in anti-Bill Shorten content. Their memes were pumped out quickly and were intentionally basic - a strategy about pure volume to flood social media feeds, described as "water dripping on a stone".

"It's a churn for content. They don't want pages to be empty," said a former Liberal campaign strategist, who asked to remain anonymous to freely discuss communications plans.

"But a lot of it is chaff. They're filling airspace. Much of it isn't focused in any way."

Staffers and strategists across both campaigns have expressed a mix of delight and confusion at various memes shared by their party. They noted campaigns often brought in external communications firms to advise on digital strategy, which one experienced operative said was part of the reason why the parties sometimes threw up "disjointed random shit that is totally different" to their normal fare.

The memes come in a variety of formats and pop culture references but are relentlessly singular in their messaging.

The Liberal memes usually deploy an unflattering photo of Albanese making a funny face and cast doubt on his economic credentials and competency, and often shoehorn in the word "flip-flop" (or even just a pair of thongs).

Labor's memes lean heavily into Morrison's Hawaiian holiday, accusing him of shirking responsibility or "not doing his job".

The Liberal strategist, who worked on multiple federal elections, said previous campaigns had used memes to encourage specific actions - activating apathetic supporters, or getting people out volunteering. But he said in 2022 the content from both major parties was mostly a play to "just occupy the battlespace" of online feeds.

"They're treating it like electronic advertising, just dumping it out," the strategist said.

"Parties producing this looks like a monumental waste of time. Part of the strategy is 'come for the laughs, stay for the facts'. Is it working? I doubt it."

Bruns said part of the approach was "get them in with a meme, to stay around for the more straightforward advertising" and subliminally seed campaign messages into the electorate. Another part of the strategy is gaming the social media networks - hoping that funny or engaging content will be shared by existing fans to reach people who don't follow the party's pages.

"This meme culture is quite widespread, it's not just young people," Bruns said.

"The generation that grew up with The Simpsons is in their 50s and 60s."

McSwiney, who is researching the use of political memes through this campaign, said the parties were also looking to a "growth hacking" strategy, hoping social media algorithms would boost their other posts into more feeds once some get high levels of organic engagement.

The other side is paid advertising. Labor does not appear to have boosted their memes with advertising dollars on social media, instead spending to promote professionally made negative ads on Morrison or graphics painting Albanese as a positive leader. But the Liberal party's Facebook page, with 283,000 followers, is putting money behind many of their memes.

Facebook ad library data shows how different memes are targeted at different demographics, a few hundred dollars a time. One version of a meme depicting Albanese as Dory - the forgetful fish from the Finding Nemo films - with the tagline "Lying Albo" was distributed overwhelmingly to those aged 50 and above in Queensland and Victoria. A separate version of the same gag was targeted at young men in New South Wales.

One video appearing to show Judge Judy criticising Albanese was shown to older women in Queensland. A meme depicting Albanese as James Bond without an economic plan was served to men of all ages in NSW and Victoria.

Bruns and McSwiney said some of this social media advertising might not be entirely an end in itself, but instead a cheap way to run "A/B testing" or real-world focus groups.

"You run several different versions and see what the electorate responds to," Bruns said.

"We must be careful not to read a fully formed strategy into all of this. Some might just be an attempt to put a lot of things out and see what tracks."

There's at least a few examples of memes crossing over into the real world. After the Liberals ran a Forrest Gump post on 3 April, Morrison told a press conference on 20 April: "You just never know what you're going to get."

McSwiney called it a "low-energy saturation approach".

"You keep pumping out so much content and hope one sticks," he said.

"It costs you nothing, it takes three minutes on your phone to pump out these memes."

But Tony Story, who was head of digital to the former NSW premier Mike Baird, said he doubted the maelstrom of memes would shift many votes.

"Who is the audience for this stuff? Almost certainly not the people who will decide the election," he said.

"No one has, nor ever will, meme their way to election victory."

Story said he saw much of the social media activity as just trying to "extract a few likes" and "cheap laughs" from existing fans of the parties.

"People assume there is a deep sophistication in campaigns. It's depressingly not the case," he said.

- by foxnews

- descember 09, 2016

United Airlines flight returns to Hawaii after concerning message found on bathroom mirror; FBI investigating

United Airlines Flight 1169 to Los Angeles returned to Hawaii after a "potential security concern" aboard the plane. The FBI and police are investigating.

read more