- by foxnews

- 14 Mar 2025

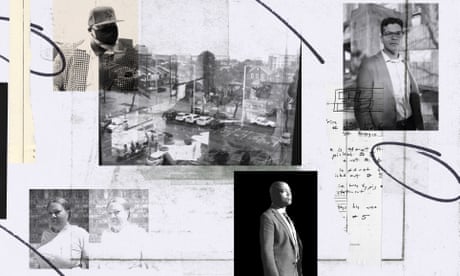

Inside the Division: how a small team of US prosecutors fight decades of shocking injustice

Inside the Division: how a small team of US prosecutors fight decades of shocking injustice

- by theguardian

- 07 May 2022

- in news

In June of last year, assistant district attorney Bidish Sarma sat before a pile of paperwork, more than 1,500 disorganized pages tall, rummaging for answers.

The name Kuantay Reeder had not been mentioned in public discourse since July 1995. Then, buried in the back of the Times-Picayune, a short article recorded that the 21-year-old had been found guilty of murdering a man named Mark Broxton outside a corner store. The last sentence noted that the prosecution had largely relied on the testimony of a single eyewitness.

Realistically, there was little legal hope left.

He called his boss, the chief of the Orleans parish civil rights division, Emily Maw.

Few insiders gave Williams much of a chance. He had already lost in a landslide for the same job back in 2008, and only had two endorsements from elected officials this time around. He also ran for election under a federal indictment for alleged tax fraud (that he maintains is politically motivated), which many viewed as the end of his political career.

Although operating in a politically antagonistic climate exacerbated further by a new crime surge, the division has intervened in more than 150 old cases, leading to immediate release from prison in 128 instances since its creation. It has done so through a range of detailed investigations leading to resentencings, new plea deals and exonerations, making it perhaps the most active conviction review program anywhere in the US.

It was about 6.50pm.

These facts have never been contested.

Price told the court in both trials the gunman had been facing him but was standing dozens of feet away across traffic when he opened fire. Price then walked into the food store, according to trial transcripts, and saw the gunman fleeing, later dumping a jacket into a dumpster as he ran away.

A second eyewitness named Norma Varist, who initially implicated Reeder, refused to testify in court and was jailed for contempt, in front of the jury, because of her refusal at the second trial. But hearsay evidence related to her identification was admitted without contest.

But Price stuck with his story.

Reeder recalled watching Price testify that day.

Three defense witnesses testified that Reeder had been playing basketball at a nearby housing project when the shooting occurred, and had eaten a meal with his mother after.

The jury deliberated for less than two hours.

He remained unaware for three decades that he had been convicted by an 11-1 non-unanimous jury. Louisiana has allowed such decisions because of a Jim Crow-era law designed to dampen the power of Black jurors; non-unanimous decisions have disproportionately disadvantaged Black defendants ever since. In 2020 the US supreme court ruled the law unconstitutional.

Reeder was taken to Angola prison, the sprawling maximum-security facility built on the grounds of a former plantation. And for his first 11 years inside, he was made to work out on the fields, tilling soil on the same land once toiled by enslaved people.

It was the exoneration of John Thompson, a Black man who spent 14 years on death row after being wrongfully convicted of murder and armed robbery, which brought the chronic issue to national attention.

In a rare interview at his home, Connick, now 96, sat at his desk, smoking cigarettes as he spoke.

He pointed to a hand-painted dove, a symbol of the Holy Spirit, that hung above his mantle.

Kuantay Reeder had grown up in a tough neighborhood, the Fischer Projects in Algiers, and was no stranger to the harsh realities of life there. But the violence he witnessed in prison continued to shock him. From the time he said he was beaten by the police officers who initially questioned him back in 1993 to when he saw men crushed and cut in prison fights, and when he himself was involved in brawls during spates of torrid violence.

His wife, Vanessa Scott, had returned to him after a few years apart. She came to visit once a month, a five-hour round trip from New Orleans. They would sit in the visitation room together for a few hours, holding hands.

But even as his mind eased on occasion, he still thought about his case. How he believed his name had been bandied around the projects, and how police had initially essentially pursued hearsay and gossip as a means to investigate. Reeder had known Broxton as a child, he had always said, but had not seen him in years. And no motive had ever been clearly corroborated at trial.

The alternate suspect matched the physical description given by Price closer than Reeder. And he had, according to his ex-partner during a police interview, threatened Broxton from inside prison over a romantic dispute. He had later called her minutes after the shooting to say Broxton had been killed, according to testimony. She had earlier told police Bird had told her how many times he had been shot and where on his body the shots had landed.

Reeder had made Brady claims throughout the post-conviction process, after his case was taken up by the veteran defense attorney Sheila Myers at the Tulane criminal justice clinic. She had been given access to a few hundred pages of documents under public records requests, and later uncovered that Earl Price, the sole testifying eyewitness, had a federal conviction for lying on a firearms application that had not been disclosed at trial.

Here, hundreds of small drawers contain tens of thousands of index cards. Each card a criminal case, documenting a record on microfilm. The drawers of microfilm, too, were damaged by humidity following Katrina, leaving many stinking of vinegar as they slowly decay.

Until midway through last year, the division relied on a now defunct Konica Minolta MD 6000 microfilm machine (spare parts had to be ordered from eBay). Each page was scanned individually by volunteers. Eventually, following a donation, a modern machine was purchased.

But in there, nestled away even further, were the handwritten notes discovered by Sarma that almost took his breath away.

They revealed, in perfectly formed handwriting, that Price had on two separate occasions insisted that he had identified another number in the lineup during pre-trial interviews.

The number corresponded to the alternate suspect, Bird.

In interview notes written on 19 October 1993, Price told investigators he had signed photograph No 5. (See note here.)

(The photographic lineup presented at trial and shown to the jury, has been lost.)

None of this information had been disclosed. Instead, it laid buried in a file for almost 30 years as Reeder fought to prove his conviction was unjust.

Unreliable eyewitness identifications have contributed to 69% of wrongful convictions overturned by post-conviction DNA evidence, according to the Innocence Project. (There was no DNA evidence in the Broxton case.)

They discovered that Price had died in August 2020, leaving many questions unanswered. Why had he insisted, on two occasions, he identified another photograph? Why had he changed this account at trial? And why was this potentially vital inconsistency never disclosed to the defense?

Sarma spoke to the old prosecutors, who largely defended their handling of the case.

Sarma also confirmed that the alternate suspect had been released from prison the day before the shooting.

The suspect was also interviewed by the civil rights division as part of their reinvestigation.

Mary Green had attempted to forget about the case from the day of the guilty verdict. Broxton was her oldest son. A handsome, fresh-faced 21-year-old, denied the opportunity to fulfill his promise as a father because of a senseless crime.

Although he had fallen on hard times before the shooting, she had always prayed he would find his way. He left behind two daughters and another yet to be born.

Green worked as a city bus driver when her son was killed, and was driving a route nearby when the shots rang out.

But as the new facts were divulged to her, she felt a creeping sense of devastation, that the justice system had failed her and her son as well.

A question lingered in her mind over the original prosecution.

But it would be left for a judge to decide.

It would not be the last time the former DA publicly criticized the work of the division.

Throughout his investigation into the Reeder case, Sarma worried about how the public might perceive the work.

Cannizzaro has forcefully denied any involvement. A trial date is now set for July, and if convicted, Williams faces suspension from office.

On a gray, humid morning in December last year, Reeder appeared in the same courtroom where he was sentenced in 1995. The wooden public benches were almost empty and Reeder was appearing from Angola prison on a Zoom link.

Her soft voice bounced around the room. She spoke directly to Reeder, as he looked intently down the camera.

As Green continued to apologize, Goode-Dougles intervened, telling her not to blame herself.

The judge tossed the conviction under Brady.

Sarma addressed the Broxton family directly.

He turned to Reeder.

The court adjourned as sobs dissipated into the open air. Reeder became one of six exonerations the Orleans parish civil rights division secured within its first 12 months.

Later that afternoon, Reeder walked out the gates of Angola prison, clutching two small bags with his possessions. Vanessa Scott, his wife, sat inside her car waiting for him.

As they drove back home, along the winding country highway, they stopped at a church on the roadside, he recalled. The doors were locked, so Reeder bent down on the steps in the open air and prayed.

- by foxnews

- descember 09, 2016

Southwest flyers fire back over airline ending free checked bag policy: 'Nail in the coffin'

Southwest has customers sounding off after the airline announced an end to its checked bag policy, leading some flyers to say they'll "boycott" the airline.

read more