- by foxnews

- 05 Apr 2025

‘We committed the murders. We took the children’: 30 years on from Paul Keating’s Redfern speech

‘We committed the murders. We took the children’: 30 years on from Paul Keating’s Redfern speech

- by theguardian

- 10 Dec 2022

- in news

Thirty years ago today, the then prime minister Paul Keating gave a speech in Redfern.

It is an unassuming description of what is often referred to as the greatest oratory in Australian political history.

"The Redfern address" was the first time a prime minister spoke about the dispossession and violence Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had survived.

Guardian Australia asked those who were on the stage with Keating, and some of those who were in the crowd, to share their memories of the day and reflect on the legacy of those words.

On the stage were Sol Bellear, Stan Grant and Matthew Doyle.

Sol Bellear AO was a giant of the Aboriginal community. The Bundjalung man was a founding member of the Aboriginal Medical Service Cooperative, the Aboriginal Legal Service and Aboriginal Housing Company. As the deputy chair of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, Bellear introduced Keating to the crowd. Bellear died in 2017, and this is an edited extract of the last interview he gave, at Redfern Park, reproduced with kind permission of his family.

"People say that they remember where they were at the time. I was right there on stage with him, and along with Stan Grant. Stan Grant, of course, was the MC. The day itself was just something unbelievable. It was just a gathering, a prime minister giving a speech. Yes, it was in Redfern; yes, it was about Aboriginal people. But then into the speech, it just erupted. I mean, that speech would have to be one of the most brilliant speeches ever, in Australia, if not the southern hemisphere.

"When he got to the part where he said 'we took the children from their mothers', that's when the crowd erupted. Aboriginal people, non-Aboriginal people, they just knew that this man is very, very genuine; this man as the prime minister and this man's government had made a very, very fair dinkum commitment.

"[Afterwards] I think Paul Keating, prime minister, or Paul Keating, citizen, he knows when he's given a great speech. He knows when he's got the public there along with him. All through that, he had to pause about 10 times for the rest of the speech for the applause that he got. He was buoyed.

"We went down to the town hall for a reception there after the speech and he was just on cloud nine. Normally, he'd come up and say how did it go, like everybody else, or what did you think? He knew that he was on a winner. He was just on cloud nine for the rest of the day, and deservedly so.

"Keating's speech was the most significant speech, prime minister or not, ever made to Aboriginal people in Australia, and not just to Aboriginal people, but to all of Australia. There was no guilt in it. There were no words there to make people guilty. I think, on the day, the non-Aboriginal people in the audience applauded and knew that.

The Wiradjuri broadcaster and author was MC on the day.

"It was so short, as prime ministerial speeches go. It was done in minutes. But you don't need long to tell the truth.

"Remember what he said. The problem starts with us. We did the dispossessing. We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life. We brought the disease and the alcohol. We committed the murders. We took the children from the mothers.

"Never before had those words been said in that way by a prime minister. So simple. All over in minutes. But it had taken two centuries to say.

"I was on the stage as Paul Keating stepped up to the microphone. It is captured forever on video. But I don't need to watch it to remember its impact.

"There was a murmur around Redfern Park.

"Families were sitting in the sun. Old people. Children. They were talking amongst themselves.

"Then something happened. A quiet fell. Those words started to land.

"Then a cheer when Keating told the truth. Because we knew these things. Those of us there that day, we knew what history felt like. We wore it in our souls and on our bodies. We knew the lies of Australia. The myths of settlement and peace. We knew that the First Fleet was an invasion. We knew that the explorers were raiders. Plunderers.

"These things had been buried in the Great Australian Silence. Australia was a monument to forgetting. It still is. There are still things we would rather not say aloud.

"Paul Keating was on the stage, but not alone. There were ghosts there that day. The spirits of those who had always known the truth. Bennelong was there. Patyegarang was there. Barangaroo was there. Pemulwuy was there.

"These people watched the tall ships come. They had heard the first gunfire. Saw the disease.

"Eddie Mabo's spirit was there. Just six months earlier the high court had recognised what he had always known - what we had always known - this is our land.

"I have wondered over the years about how I felt that day. What it meant to me.

"Paul Keating told me nothing I did not know. But there is power in words. To hear these truths spoken meant we were seen. It meant that my parents, my grandparents were seen. We mattered. Our truth was undeniable.

"I have a copy of that speech. It shows Keating's own handwriting; words crossed out; thoughts written in the margins.

"When I left Australia, I knew that speech could not come with me. They were words of this land. They needed to stay here, to echo here. I gave the framed copy of the speech to my friend Jeff McMullen.

"That speech still hangs on Jeff's wall. A reminder of a day and a promise and a truth.

"It is our own personal covenant, I guess. That one day as a nation, we may even honour that truth."

Matthew Doyle is a descendant of the Muruwari people from the Lightning Ridge area of NSW and grew up in southern Sydney on Dharawal land. Doyle is a professional musician, composer, dancer, choreographer, cultural consultant and educator. In 1992 he performed before Keating came up to speak.

"I'd been asked to come and play the yidaki to kick off the day. I'd done a lot of major performances everywhere but it was really an honour to be able to start the day off. And in hindsight, I had no idea how important the prime minister's speech would be.

"I was playing a traditional song that I'd learned, which went for about three and a half minutes. But what I decided to do was keep going and repeat it. Meantime, the prime minister's standing there waiting, and I have no idea why but I thought 'nah, I'm gonna make him wait'. Get the crowd in, get the crowd settled. So I finished and then he came up. And no one told me what to do next. Like, do I exit the stage? Do I stand there and listen to the speech?

"And that's what I decided to do. I just stood back from the microphone and listened.

"Bangarra were there that morning. This was the beginning of Bangarra, this was one of their first major public performances as well. So I had friends and familiar people around me as well. I just remember painting up and thinking it was a pretty big deal.

"Even before Invasion Day, [Redfern] park was a pretty special cultural place anyway. For the Gadigal mob and other clans, it was a gathering place where ceremonies took place. It was a source of water, as well. A pretty important place, way before we got invaded. So it was highly appropriate that that speech took place in that park. Anywhere else, I don't think it would have had the same impact.

"What I remembered most was [feeling] relief that finally, a head of government has admitted the wrongs of the past and told that to our faces. And then later on thinking, OK, yes, that's true, admit the past, all the wrongdoings, but now I want to hear about what are you going to do to fix it.

"We haven't moved that far forward. There's still a long way to go for us to have equality. The voice to parliament is a start. The referendum is a start as well. But for us as Indigenous Australians there's still a long way to go. Before we have equality, and justice in all forms in our lives."

Distinguished Prof Larissa Behrendt OA is the Director of Research at the Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning at the University of Technology Sydney, an award-winning author and film-maker. Behrendt was in the audience as a recent law graduate.

"It was a curious thing to hear that the prime minister was coming to Redfern. It was a time when taxi drivers wouldn't stop there. I attended the Redfern Park speech not knowing what an historic occasion it was. And looking back, I am still amazed by the decision to give this important speech in front of an audience known for its confrontation and combativeness. This was not a community who could be politely curated. If you were coming to address them, you had better mean it.

"I had just finished law school and was planning to study overseas. I had been through a school system that didn't teach about Aboriginal history and sat through classes as the granddaughter of a woman removed as a young girl from her family under the assimilation policy where my classmates were ignorant of the fact that there were 'stolen generations'.

"They were taught that Australian history started in 1788 and that my people had vanished into the mists of time. There were no Naidoc Day celebrations; there were no acknowledgments of country.

"So, standing in Redfern Park hearing the Australian prime minister say the words, 'We brought the disasters. The alcohol. We committed the murders. We took the children from their mothers. We practised discrimination and exclusion,' struck me immediately as momentous.

"I felt like those words were said directly to me - acknowledging the silences that I had felt excluded by. It left me naively optimistic. The conversation was changing. The tide was turning.

"I could not foresee was the backlash that would follow, the claim that 'the pendulum had swung too far.' I was to learn that for every high-water mark like the Redfern Park speech, there is an ebbing tide. But I still look back at what it felt like to be there in Redfern, on that day, hearing Keating's heartfelt words and it reminds me of what is possible and of what hope feels like."

Lorena Allam is the Indigenous affairs editor of Guardian Australia. At the time she was a newsreader and journalist at Triple J.

"I'd finished my morning newsreading shift when a friend called to say I should come down to the park. The PM was going to give a speech.

"It was a family event to launch 1993 as the UN international year of the world's Indigenous peoples. It was sunny and hot. There was a big crowd, dancers painted up ready to perform, schoolkids in their uniforms.

"I was at the side of the stage under a stand of big palm trees in a sort of media corral, with friends who were working at the event as media advisers to politicians, journos, camera and sound people. We had all been at these type of events before, where pretty speeches got made, so we weren't truly paying attention.

"When Keating got up, people were a bit sceptical. They just wanted to enjoy the day and have some fun and let the kids play. They were all still talking to each other when Keating started to speak, so his opening words were a little drowned out.

"Then he started to say these extraordinary things. 'We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life.' People went silent. 'We committed the murders.' Murmurs of surprise. The mood began to change. 'We took the children from their mothers.' There was cheering.

"Keating used the word 'we' in a way I hadn't heard a politician use before - as an admission of culpability, a call for responsibility. A plea for empathy and understanding. For so long, when politicians used the collective 'we', we knew they weren't thinking of us. We were invisible, our lives so far beyond the comprehension of everyday Australians that we did not count.

"That was when it dawned on me something important was unfolding. Here was a prime minister, the first - and so far only - leader prepared to speak these truths. And he had come to Redfern, the heart and soul of the Aboriginal community, to do it.

"He spoke to everyday Australians, too. And his message was powerful. He asked them to imagine justice.

"It's a speech that hasn't been equalled. It allowed us to dream that Australia was capable of coming to terms with its history. Of course that dream was snatched away under the long, hard Intervention years that followed. But on that sunny day, listening to those words, it felt like a moment when the tide began to turn inexorably towards truth.

"Thirty years later, we are again at a national turning point where Australians are being asked to imagine justice."

Meade is Guardian Australia's media writer and was a journalist at the Sydney Morning Herald in 1992, sent to report on the speech.

"On the morning of Thursday 10 December I was assigned by the news desk of the Sydney Morning Herald to cover the launch of the international year of the world's Indigenous peoples, at which prime minister Paul Keating was to speak.

"The Herald editors did not expect a big story to come out of what was essentially a community event organised by South Sydney council, and the federal political reporters were unaware of what was to come.

"As the kids ran around Redfern Park, there was no sense that this was to become an iconic event in Australian history.

"The park was packed with locals of all ages from the Redfern Aboriginal community on what was a very hot sunny day.

"There were Sydney-based media on the ground rather than the usual Canberra media pack that follows a prime minister.

"As Keating began his 17-minute address, the crowd was restless but it soon became clear this was no run-of-the-mill speech and they became more attentive.

"It 'starts with us, the non-Aboriginal Australians,' Keating said, flipping the narrative and detailing the white atrocities.

"I had that rush journalists get when they recognise a good story: it was the strongest statement ever made about Indigenous people by an Australian leader."

- by foxnews

- descember 09, 2016

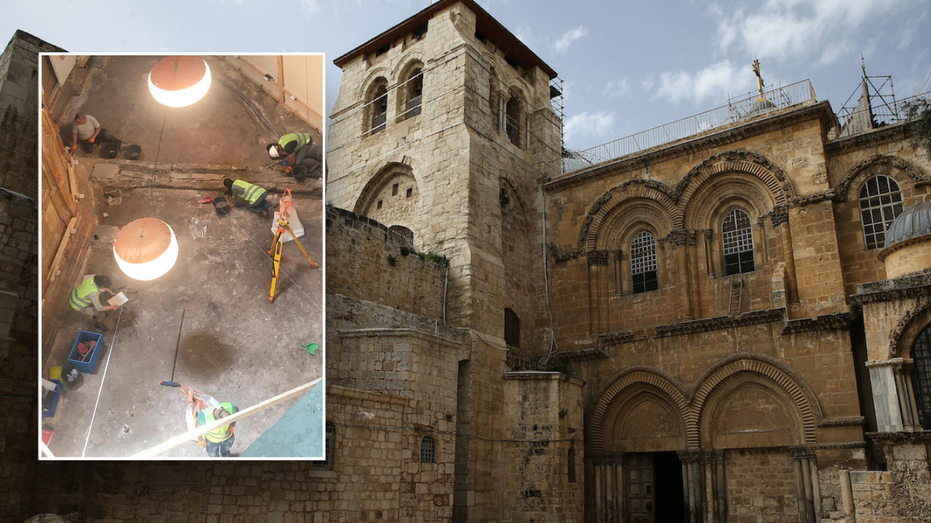

Excavation near site where Jesus was crucified and buried results in ancient discovery

Proof of ancient olive trees and grapevines, consistent with a Bible verse, has been found at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, an archaeologist confirms.

read more